Between Public, Semi-public and Private

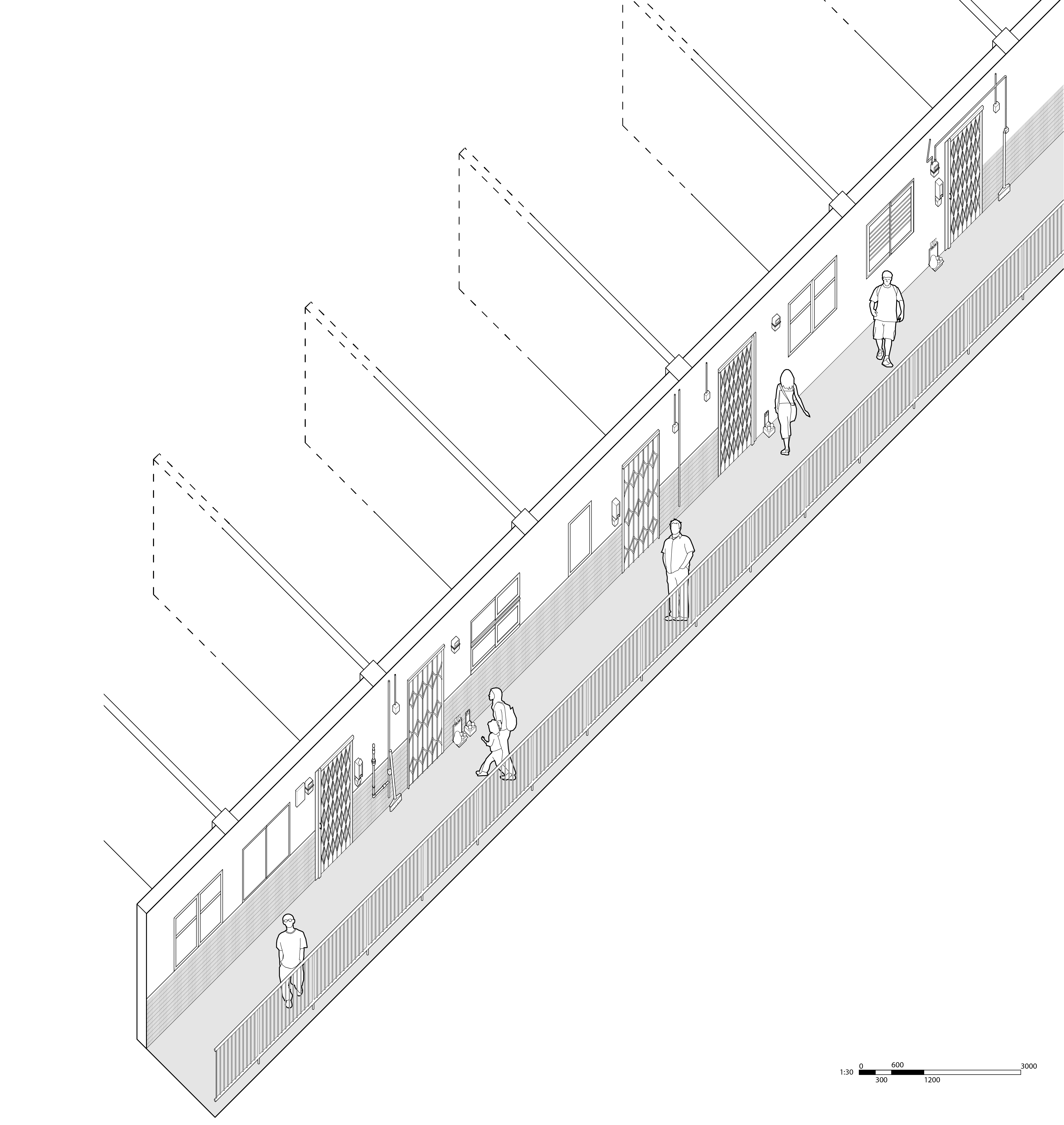

While Wah Fu Estate residential units were innovative when they were built and provided for residents’ needs, there were still a lot of everyday routines that residents tended to perform in the public areas outside their private flats. Some residents may consider any space outside their flat’s front door as public; some feel comfortable to leave personal items in the corridor immediately in front of their flat’s front door, claiming that area as their own; some may even place personal items in the communal spaces outside the residential block. Residents’ different attitudes and behaviour make up a rich seam of information revealing how people interpret different hierarchies of public and private space.

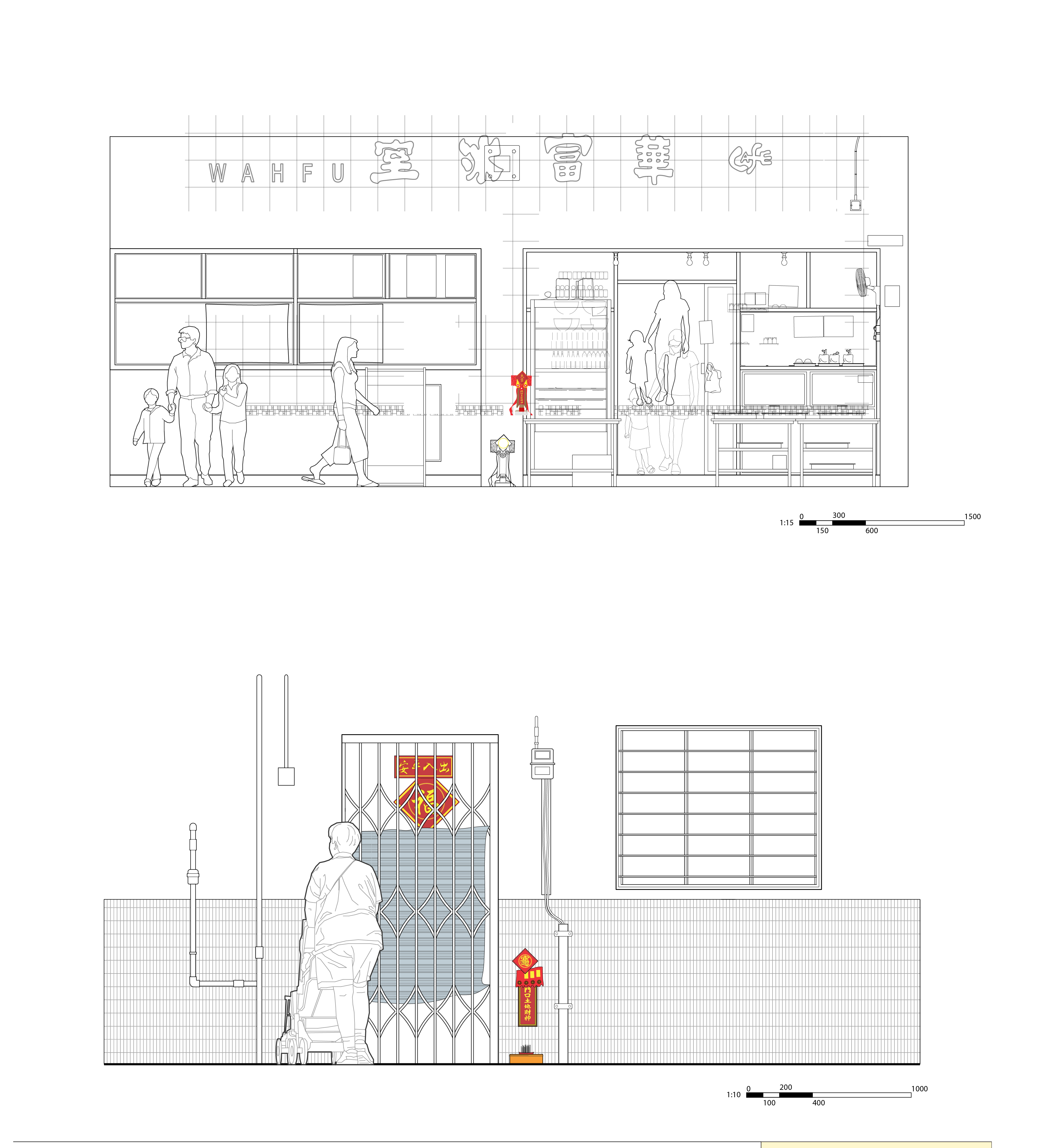

Elevation showing how residents personalise their unit doors along the corridor

Between Public and Private

One phenomenon observed in Wah Fu Estate and many other public housing estates is the habit of many residents to put their Tou Dei — the earth deity that protects the household — at the corridor side of the lower corner of the front door of their flat unit. The corridor is officially considered public space not intended for personal items, but the Tou Dei is usually placed right at the entrance of the living space to guard against any ‘bad elements’ entering the residential flat, and would not make sense if placed inside the house. The location of the Tou Dei reveals how residents view the threshold between public and private space.

Another phenomenon observed along Wah Fu Estate residential corridors concerns residents’ storage habits – some residents leave their shoes, umbrellas, and other items outside their residential flats. This may be because it is more convenient to access these items when leaving the flat, or it may be because of hygiene issues that these items are left outside the door. Besides indicating the residents’ mental thresholds concerning ease of access and cleanliness, such habits demonstrate the nature of the social dynamics between neighbours. Not all neighbours may tolerate others leaving personal items outside the door, although of course this will be dependent on the quantity of objects. The number of items left outside the door may indicate what is socially acceptable, with further accumulation possibly leading to complaints or disputes. This behaviour also shows the extent of trust among neighbours as no one would steal other people’s items, revealing a hidden neighbourhood watch already in action.

Between Semi-public and Public

The communal playgrounds and outdoor seating areas in Wah Fu Estate are officially for the entire community and are not lockable so anybody can use them at any time. In practice, residents are more familiar with the playgrounds and outdoor seating areas just below their residential blocks, and some may psychologically feel entitled to extend their household activities into those areas, for example sun-drying their winter blankets on a sunny day.

These residents can often view the communal space from their flats, and are able to make sure their personal items are safe. Such a visual connection gives them a sense of security and community. As a result many residents may consider such communal spaces as semi-private and semi-public, but not truly public.

The dynamics of the psychology of ‘which space is yours and which is mine?’ can also be observed in the case of residents collecting herbs and fallen flowers from plants and trees in communal areas for future personal consumption, then arranging to dry them on large shared canvas sheets set out in the communal areas. This practice mirrors how a gardener might pick herbs and flowers from their own private garden. Although the context of Wah Fu Estate is very different, the origin of this practice is understandable in the same way. Similarly, in the residents’ minds, the communal space including the plants growing there, are part of their extended private living space.

In the early days of Wah Fu Estate, when making a living in Hong Kong was hard and most people lived frugally, this practice would have been socially-acceptable as long as there were mutual agreements to avoid individuals collecting herbs excessively, and to ensure fallen flowers were shared fairly. Since the HKHA introduced its ‘Marking Scheme for Estate Management Enforcement’ in 2003, such practices have become administratively problematic.

Axonometric drawing showing how the corridor is a space between public and private

Photographs of the rooftop playground and corridor being used for sun-drying laundry

What Do We Learn From These Examples?

While Wah Fu Estate had a series of communal spaces for residents to use from early days, many of them were not too prescriptive in the sense that they could be used for multiple functions or up to users’ interpretations. Such flexibility allowed for residents’ improvisation, and in the process of personalizing some of the spaces, it helped develop residents’ sense of ownership to the place. These phenomena give characters to the place, and tell stories and personalities of who the users are.